Youth Football Is a Moral Abdication

Today’s concussion crisis gives the misimpression that the sport’s hazards were only recently discovered. In fact, they’ve always been evident. So why do adults let children play?

In the 1890s, the Chicago Tribune began to sound the alarm about a dangerous new sport. Unlike in baseball, cricket, or other popular activities of the day, teams of young athletes repeatedly collided with one another as a key component of the emerging game. The quest for victory resulted in frequent impacts to opposing players that would “strain their hips, break their noses, and concuss their brains.” Should football overtake baseball as America’s national game, the Tribune advised, it would need to be profoundly reformed. Otherwise, the sport would “physically ruin thousands of young men.”

More than 120 years and many thousands of severely injured young men later, football sits, as the sports economist Michael Leeds once put it, “like a colossus across the landscape of American sports.” Despite both established medical knowledge and commonsense understanding that engaging in repeated collisions poses extraordinary physical hazards, adults promoted football for boys of all ages throughout the 20th century. Football not only overtook baseball as America’s most-viewed televised sport, but it also became by far the most popular sport played by American high-school boys. Feeder systems quickly developed for their elementary- and middle-school counterparts. Today, children as young as 5 can begin tackling one another. Billions of dollars in television contracts, the very identities of major colleges and universities, and the Friday-night rhythms of communities across the United States are all tied to the gridiron.

In the past decade or so, the early deaths of NFL players by suicide and other causes—not to mention the growing body of scientific literature on chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a brain ailment associated with repeated concussions—have drawn new attention to the dangers of tackle football. Today’s concussion crisis might give the impression that these dangers were not well understood in the past. In fact, the physical harms associated with the sport have never been in any doubt. To continue to feign ignorance of them—to keep letting boys not yet in their teens play tackle football—is not just unwise, but an abdication of moral responsibility for children’s welfare.

Since the dawn of football in the late 19th century, a series of fatality reports, medical studies, and journalistic critiques have periodically coalesced into a national conversation about the sport’s safety. Especially at moments when other major elements of American culture came under scrutiny—for instance, during the Great Depression and amid the massive social transformations of the early Cold War years—the undercurrent of concern about the sport bubbled up: Was such a risky activity ethically acceptable for schools to host and for children to participate in?

But time and time again, football’s supporters found a way to ignore the doctors and educators who warned of concussions and other debilitating injuries. Whenever the sport faced a serious public-relations crisis, coaches and administrators found ways to tweak the rules or adjust the equipment in an effort to reduce the most catastrophic harms. As the popularity of the sport grew, fans simply accustomed themselves to, and even cheered on, the ruinous hits that occurred in plain sight. Parents who sought, in countless other ways, to minimize risks to their sons eagerly signed them up to play. And the wrecked knees, broken necks, dislocated shoulders, and cumulative brain damage kept on coming.

“I believe in outdoor games,” President Theodore Roosevelt declared in 1905, “and I do not mind in the least that they are rough games, or that those who take part in them are occasionally injured.” An enthusiastic football fan, Roosevelt intervened after countless severe injuries and scores of deaths appeared to threaten college administrators’ willingness to condone the sport. After the president invited officials from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton—schools that were then prominent in the sport—to the White House to discuss football’s brutality, some rules were changed to limit the riskiest plays. In 1906, an athletic association, now known as the NCAA, was established to provide oversight. Yet leading medical organizations emphasized at the time that the physical hazards of football remained enormous. Acknowledging that the recent reforms might result in fewer fatalities, a 1907 Journal of the American Medical Association article nonetheless characterized football as a gladiatorial sport whose risks far outweighed its benefits. This was especially the case for children whose bodies were still developing. “Football is no game for boys to play,” the journal declared.

With several brief exceptions, such as a temporary ban on football in New York City high schools in 1909, coaches and administrators largely ignored this medical advice. Instead, American schools embraced football, contending that the sport imparted crucial leadership skills to boys who were expected to become future business and military leaders. As one physical educator put it in 1922, “Athletic activity is the best substitute for war.” In 1927, The New York Times reported that 17 players ages 15 to 22 had died playing football that year. But the newspaper also reminded readers that “the game is being played on a gigantic scale in all parts of the country” and that the death toll was thus less alarming than it might seem. Indeed, in 1928, The Washington Post dubbed football the “kingpin of interscholastic sports,” a title it still holds today.

Doctors and educators continued to look askance at the collision sport’s dominance in schools. The yearly deaths only hinted at the much larger number of what Henry O. Reik, the editor of The Journal of the Medical Society of New Jersey, described in 1931 as “severe and permanent injuries.” Reik urged the abolition of college and high-school football. Even football’s supporters acknowledged that the sport was unusually dangerous. In 1936, Mal Stevens, then the head football coach at NYU, told the New York Academy of Medicine that football was by far the most hazardous sport on offer in American schools. According to data compiled by NYU researchers in collaboration with insurance companies, football players experienced 88 accidents per 1,000 exposures—a rate eight times higher than that of polo, the second-riskiest sport.

Of these hazards, brain injuries were well known to be of serious concern. In 1929, Eddie O’Brien, a doctor and football official, urged that administrators require a physician to attend all school football matches, citing examples of players knocked unconscious or “out on their feet” who were allowed to remain in the game. He used the term punch-drunk to describe “the condition caused by head injuries and lack of medical attention.” The phrase, which referred to the state of confusion resulting from many hits to the head, was mostly associated with boxing. But physicians clearly understood that repeated blows in football could also cause significant cognitive harm.

Given the risks, a 1938 Journal of School Health article advised against football for boys under 16 years of age, noting that “more concussions occur in football than is generally realized.” That same year, Augustus Thorndike, a physician who played a key role in the development of sports medicine, complained that most laypeople were unaware of the serious complications that might result from “a simple concussion of the brain.” In the decades to follow, many other medical experts would express similar frustration with Americans’ willingness to disregard the brain’s vulnerability to repeated impacts. In 1951, the neurologist Frederic Gibbs lamented that children were “encouraged to addle their own brains with repeated concussions in such sports as football and boxing.” Writing in the American Journal of Public Health, Gibbs urged that the next generation be taught instead to appreciate the importance of the brain.

To that end, in a 1952 New England Journal of Medicine article, Thorndike recommended limits on how many brain injuries athletes might sustain in their careers. He advised that athletes cease any exposure to body-contact trauma, such as football, after sustaining three concussions or experiencing more than momentary loss of consciousness at any one time. Thorndike added that “the college health authorities are conscious of the pathology of the ‘punch-drunk’ boxer.” His guidance was clearly intended to prevent such serious harms, and his recommendations were just as clearly ignored. Many young players sustained multiple concussive hits throughout their careers. They were in many cases sent back out onto the field nearly immediately after suffering brain-injury symptoms. Brain injuries were frequently minimized as “seeing stars” or “getting your bell rung.”

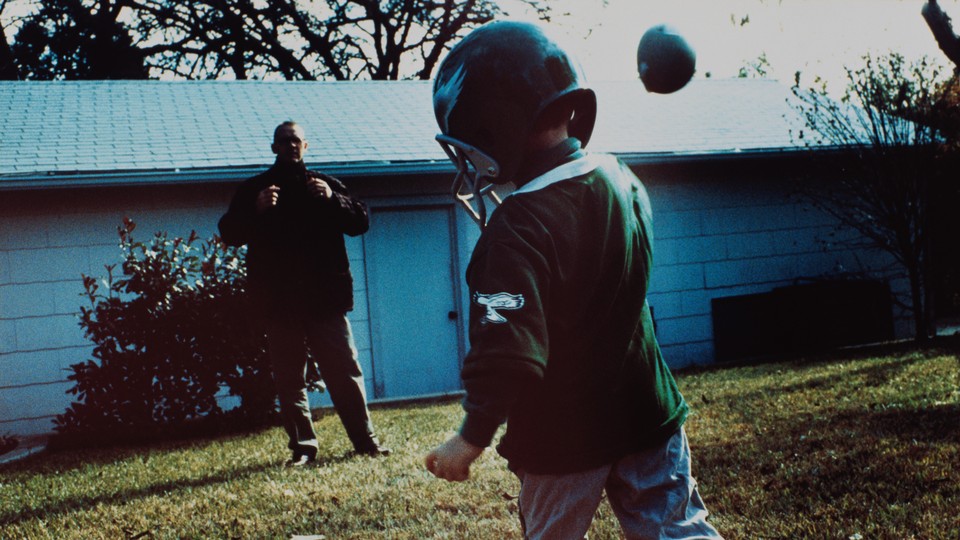

After World War II, football programs expanded to include even younger children, of elementary- and middle-school age. By 1956, The New York Times estimated that nearly 100,000 children were playing on tackle-football teams; the athletes ranged from 60-pound 7-year-olds to 160-pound teenagers.

Educators and doctors decried this trend throughout the 1950s. In 1953, attendees at a National Education Association conference voted to ban football and other contact sports for children ages 12 and younger. In 1957, the American Academy of Pediatrics similarly concluded that “body-contact sports, particularly tackle football and boxing, are considered to have no place in programs for children of this age.” While the academy may have had some success in limiting boxing matches for young children, administrators and coaches paid this guidance very little heed when it came to football. By 1964, the Pop Warner conference, a youth football league, estimated that more than half a million boys ages 7 to 15 were playing the sport under its auspices.

By the second half of the 20th century, then, many Americans boys were no longer simply playing four years of high-school football. Rather, they first enrolled in the sport at age 7 or 8 and played for at least a decade. Practice after practice, game after game, and season after season, they were subjected to repeated full-body collisions under the watchful eye of adult leaders and to the cheers of adult spectators. But the basic principles of physics continue to haunt the sport.

The rules in tomorrow’s Super Bowl will differ from those in place more than a century ago, but full-body impacts remain the essence of the sport and the major source of its dangers. The cycle of concern and denial continues: Barack Obama convened a White House summit on football-related brain injuries; his successor, Donald Trump, is a former United States Football League franchise owner who believes the NFL’s crackdown on certain hits is “ruining the game.” But the evidence of football’s harms is stronger than ever. And because children do not have full capacity to weigh the long-term risks of repetitive brain trauma, the fundamental question is: Are the risks of tackle football acceptable for adults to impose upon children?

If the current debate about concussions is to yield a safer outcome for kids than more than a century of similar conversations has, it must involve a much deeper acknowledgment of what researchers—and, really, everyone else—have already known for decades: Repeated collisions are not safe for human bodies or brains.